I was a covert intelligence officer for the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) living and operating under cover for nearly a decade. SPOILER ALERT – spying is not like you see in the movies. Yes, we get code names. Yes, we travel around the world on someone else’s dime. No, we do not drive nice cars. No, we do not get cutting-edge tech that fits inside a watch. But the most important thing to understand about spies is this – we are alone and we hate it.

In 2011 I was called to serve in a countersurveillance operation in a large metropolitan city in Asia. I was briefed only on the details I needed to know and given two pictures – one of the foreign agent and one of a fellow CIA officer traveling to meet the agent. My objective was to blend in with the crowd and keep a watchful eye from a distance for anyone taking a suspicious interest in the agent meeting.

Another difference from the movies is that spying is not glamorous. We do not wear bespoke suits and drink martinis while rubbing elbows with social elites. Spies are more like drug dealers, digging around in dark, dirty places selling treason to bad people. By virtue of the people we do business with, security is the top priority during operations. A spy that gets caught is an international incident. A spy that gets away lives to spy another day.

I tracked my targets on foot as they travelled through public venues engaged in hushed espionage. After nearly two hours, the two parted ways and I continued my look out to make sure neither was followed in their departure. Success – my mission was complete and I could start my own trip back home.

On that trip home I was struck by an urgent idea; I needed to leave CIA. Spies do not live in the real world. We operate in alias names, operate in cities where we do not live, and befriend people we do not like. Because of this parallel existence, spies only do what has to be done to maintain security rather than take risks to pursue great achievements. There are of course exceptions to the rule; the few outstanding officers who are selfless and uniquely dedicated in service to their country. But as with any other workplace, the few are not the norm.

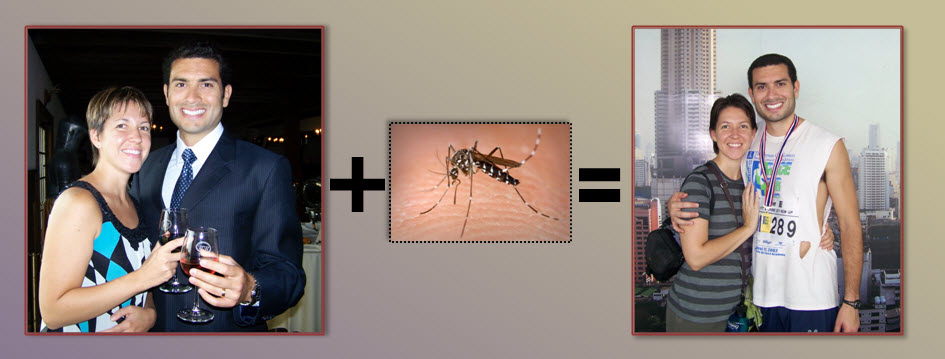

I left CIA because I believed that ambition and passion would lead to a better life while security and secrecy would end only in loneliness. I believed that I needed genuine relationships to shape me into the person I was meant to be. Complacency is a slow infection – it robs us of creativity, passion and purpose and convinces us that we cannot be who we want to be; cannot do what we want to do; and cannot achieve what we want to achieve.

Just like popular movies glorify the life of spies, popular culture glorifies the life of those who ‘fit in.’ Both are works of fiction. Many of us live like spies, choosing to conceal our identity in order to blend in with the world around us. Rather than commit ourselves to great achievement, we instead do only what we must to maintain a sense of security while surrounded by people we do not like, engaged in work that does not challenge us. We justify our actions by calling them ‘responsible decisions,’ or ‘social obligations,’ or ‘necessary steps’. In the end, however – just like so many spies – we feel alone and we hate it.

Me.Now. invites all people living like spies to realize the possibilities of a deliberate life; to write a story for ourselves. Complacency is a perpetual foe that seeks to divide rather than unite. Like a spy, we are only alone for as long as we choose to stay in hiding. Once we choose to give up our cover and step into reality, we can find a community that enables us to achieve great things and a better future.

The lesson I learned in Kyoto was that life, like a Katana, cannot be built by accident. It takes deliberate commitment and a willingness to suffer the fatigue of refinement before we can reach our fullest potential. The same steel that can rust and crack when left alone can be made powerful when folded together. I no longer fear the fire or the hammer; they are tools to make me stronger and sharper. In my community of steel, the pressure from outside forges one blade that will inspire a world.

The lesson I learned in Kyoto was that life, like a Katana, cannot be built by accident. It takes deliberate commitment and a willingness to suffer the fatigue of refinement before we can reach our fullest potential. The same steel that can rust and crack when left alone can be made powerful when folded together. I no longer fear the fire or the hammer; they are tools to make me stronger and sharper. In my community of steel, the pressure from outside forges one blade that will inspire a world.